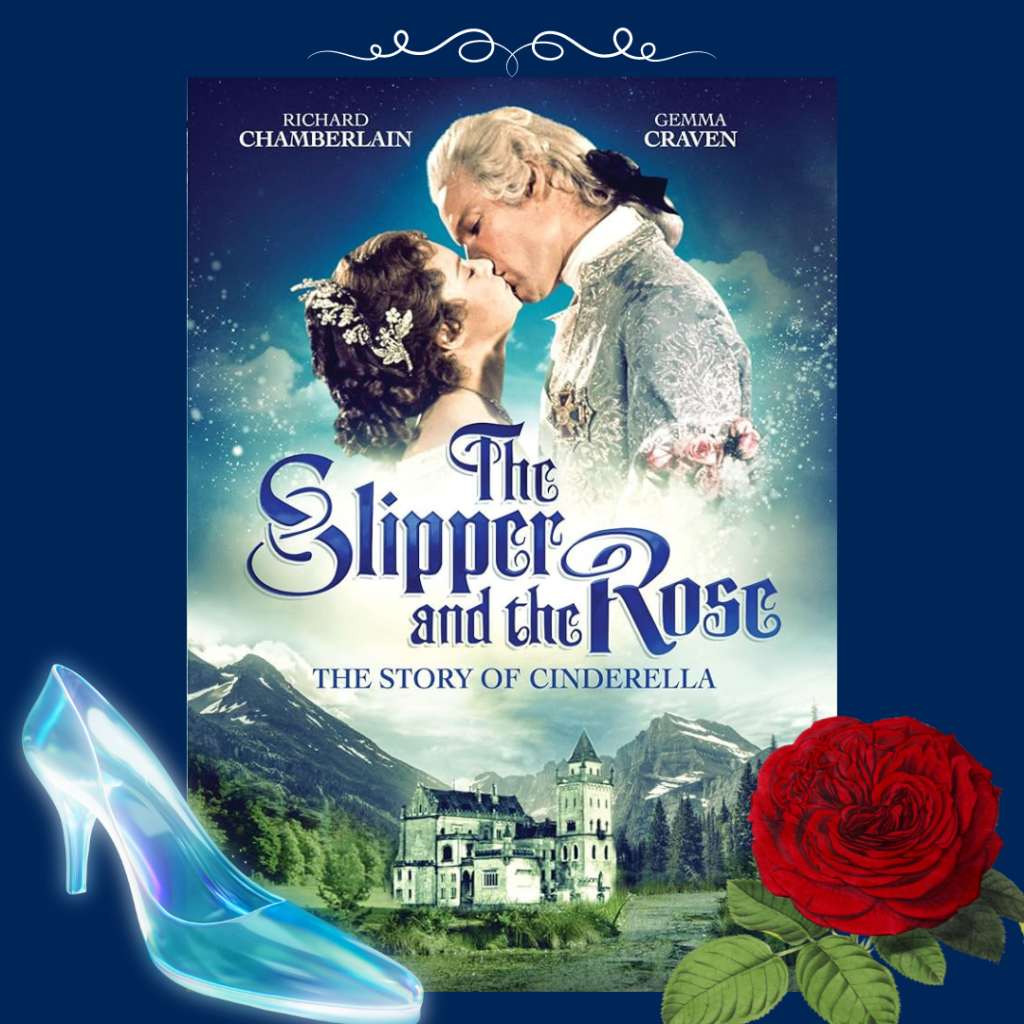

Though initially something of a mystery, the title of the Sherman Brothers’ 1976 musical adaptation of “Cinderella” is the primary clue to its value. “The Slipper and the Rose” proposes a symmetry, a duality of attention, in how it treats the main leads and their situations. And it is in these complementary and crossing paths that the film is able to create such a rich, three-dimensional tapestry of plot and characterization within the age-old fairytale. (Spoilers follow.)

The credit sequence sets the tone for a development both parallel and intertwined. A royal entourage makes its way through the winter snow, just crossing behind the path of a small funeral procession. The well-known tale makes us intuitively aware that Cinderella’s father has died, and, as she returns to her family home, the winter setting gives way to the equally cold environment created by the step-mother and her daughters.

Yet, it is the prince’s story that we are presented first; he too has just arrived home, to the disappointment of a court that had expected news of a marriage alliance. And so we begin to see the story of Cinderella take shape in the fresh voice and perspective of the prince. “Why Can’t I Be Two People?” he wonders, wishing to be free of the imposed duty of winning a wife to boost national security.

Time passes to the green renewal of spring, and in one of several ironies in the film, the attention turns to death and memory. Cinderella visits her parents’ grave, remembering the past with “Once I Was Loved.” It is a subtle courtesy to the viewer that the screenwriters are able to highlight the poignancy of Cinderella’s altered situation without having to also give excessive airtime to the cruelty of the step-family. But just within earshot of Cinderella, Prince Edward and his servant are making a visit to the royal crypt, where the prince acknowledges (at times, irreverently) the sobering realities of the empty tomb with his name on it. “No matter what I do or don’t do, no matter how I do it or don’t do it, my last appointment is here,” the prince muses, and one begins to see how this is paradoxically “A Comforting Thing To Know,” in that it lends priority and resilience to his determination to marry for love—the kind of love of which Cinderella sings.

Such interconnected focus lends credibility to the romantic weight of the dance at the ball. We have seen through the first half of the film in both temperament and story arcs how Cinderella and the prince complement each other. So when they finally, formally meet, there’s a natural sense of satisfaction and rightness. How else could a fleeting encounter be so stubbornly clung to by both main characters, were it not for the manner in which we realize Cinderella and the prince, are, to use a trite expression, “made for each other”? But are they also worthy of each other?

“What is my life to me without my love for you?” asks the prince of Cinderella in “Secret Kingdom,” and we agree, because we have seen his nascent affinity for her take shape before they ever meet. But more practically, this implied question helps illustrate that the prince is not merely a token lover for Cinderella—he is his own character, continuing to develop as a person through his love for her. Rather than becoming more self-focused because of his ideal of love being realized and then slipping away, he becomes more aware of the plight of those around him, and the fact that he is not the only one saddled with constraints. Instead of airing his own frustrations as in “Two People,” he now listens attentively as his servant, John, explains the universality of social constraints in “Position and Positioning.” And, moved by his own thwarted love for Cinderella, the prince exercises his royal position in kindness, knighting John so he can court a lady-in-waiting. And fittingly, it is John who then facilitates the prince’s rediscovery of Cinderella, echoing how Cinderella’s own kindness to the fairy godmother led to her initial encounter with the prince.

Lest it be thought that Cinderella’s arc is neglected, she receives ample opportunity to prove her own character. This is not confined to her forgiveness of the step-family—indeed, she herself acknowledges that her current happiness motivates her to such forgiveness. And why not? Who wouldn’t feel generous in the midst of a meteoric rise to security, wealth, and love? However, one might wonder if love were a little lost in the drastic reversal of her fortunes. But the film’s extended sequence between discovery and wedding permits her the chance to reveal her love is true. She accepts the king’s offer to leave the kingdom for its good, and is guaranteed the comfort of dowry and protection; she could surely count herself far better off for the ordeal and wed her choice of suitor at leisure. But instead, her love for the prince cannot bear that he should suffer anything by her forced departure, and so she orders the chancellor, “Tell Him Anything (But Not That I Love Him)”—which indeed she does. Even in an exile intentionally evocative of Rococo indulgence, all she can do is remember the prince: “I Can’t Forget the Melody.”

She is the glittering, sparkling slipper, blessed with a magical night and a determined fairy godmother, while the prince is the rose, his own identity subsumed by the emblem of the royal house and its duties. But each is more than what simply meets the eye. Notwithstanding magic, she is first and foremost true to kindness and loyal to love. The prince, despite the demands of royal impositions, remains true to transformative love and the kindness it inspires.

The fairy godmother does not arbitrarily grant wishes; neither does the prince seek to cast off the royal duty that will inexorably lead to his tomb. It is in their respective characters and choices that magic is able to intervene and the kingdom is able to survive. The film certainly does not gloss over the difficulties of royal marriages and political alliances, but neither does it insist on contrived solutions that strain desperately for the firm ground of realism. It is instead sufficient that the reality of love and kindness be the substrate for magical intervention and answered prayers—which is perhaps the real value of not just “Cinderella” but fairytales in general. As another frustrated prince has said, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” It is a clear-sighted yet unbounded belief in love that inspires the magic uniquely deserving to be included in the story of Cinderella, elegantly and comprehensively retold in “The Slipper and the Rose.”