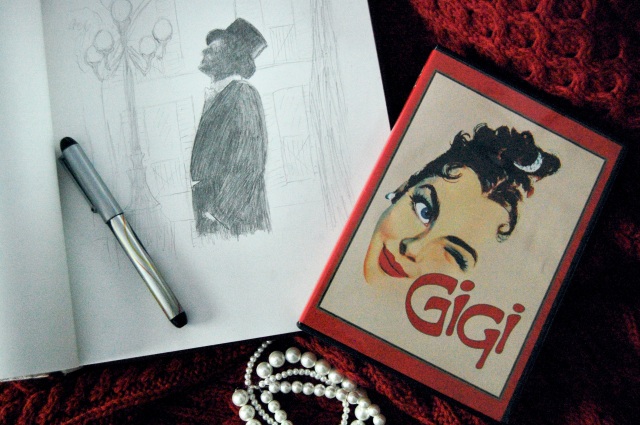

Gigi, Vincente Minellie’s 1958 frolic, uses the color of 1890’s Paris and the music of Lerner and Loewe to build to a profound illustration of the equality of love in marriage. High society of that time, and the concept of mistresses for the elite, or courtesans, is treated with veiled humor, particularly in the character of Honoré, played sympathetically by Maurice Chevalier. As the narrator says in the film’s trailer, this is a “Paris that takes love so seriously and marriage so lightly.” Yet, this very lightness gives heightened contrast to the moments when the demands of true love are confronted. (Spoilers follow.)

The vivacious title character, played by Leslie Caron, epitomizes this serious gaiety. The girl Gigi is eager for fun, while yet being prepared for a future role of courtesan by her strict but savvy Aunt Alicia (Isabel Jeans). The dichotomy is striking; the practice is spoken of in euphemisms and nods between Aunt Alicia and Gigi’s grandmother (Hermione Gingold). Yet Gigi, taking such “love” at face value, voices her opinions with remarkable frankness and clarity. It is easy to suppose that it is this honesty that first attracts Louis Jourdan’s Gaston.

Gigi is in stark contrast to Gaston’s usual companions, typified by Eva Gabor’s showy but distracted Liane d’Exelmans, whom Gaston is astounded to find unfaithful to him. After such distressing affairs, Gaston finds Gigi’s girlish company refreshing and charming–so much so, that after returning from travels abroad and finding her wearing her hair up and her dresses long, he flies into a small temper. After a pondering walk through Paris and a passionate, wondrous rendition of the title theme, he realizes he is in love with the woman Gigi has become. And so he asks Gigi to be his companion–and she refuses. The refusal is given waveringly, as she confesses to love him, but she understands well that the life that lies before her is one of uncertainty. She knows, as do the society columns, that this type of relationship is cyclical, just as it was for poor Liane. But as much as one wishes Gigi to stand firm and for Gaston to relent, it is Gigi who finally acquiesces, telling him, “I would rather be miserable with you than without you.”

However, Gaston soon discovers that this is a changed woman. She is an adoring companion, the elegant appendage her aunt trained to be, filling the role as well as anyone ever did. She is that, but not Gigi, for this new role defines Gigi merely by her sexuality, and not her complete identity as a person. Whether dining at Maxim’s or strolling in the park, the role of mistress is inadequate to contain all that Gigi is. Strangely, Gigi is no longer his, now that Gaston finally possesses her.

Once more Gaston’s temper flares, and without seeming to know how this distortion came to be, he drags a distraught Gigi home. He then retraces his steps around Paris, recounting silently, his silhouette in a constant moonlit shadow. Of all the many tuneful moments of the film, this is the most musically profound. As the score swells to an instrumental reprise of the title song, the audience knows, as does Gaston, that what he first sang out loud for all Paris to hear . . . for all Paris to see . . . is a much stronger crescendo, too deep to be spoken of in words.

To make Gigi his mistress is to destroy the Gigi he loves. They must belong fully to each other–if this belonging is one-sided, then one of them is not fully his or her self. And for Gaston, who has fallen so completely in love with Gigi (a character shown throughout to be fully herself, despite her relatives’ influence), his love cannot be fulfilled by anything less. That Gigi’s wholeness, her identity, is diminished by appearing at Gaston’s side as mistress, is the redeeming value of her weakness in having given in to his offer. While there is a disappointment in seeing her abandon her logical position of self-worth, the results illustrate in a striking way just what his request has done. It is after this realization that Gaston now upholds the logic he once found so absurd in Gigi. The standard he held up to Liane in disdain, he now willingly submits himself to, by asking for Gigi’s hand in marriage.

Though the discussions of Gigi’s aunt and grandmother are mostly serious and poignant in addressing a practice dismissive of women, much can be made of the sexism delivered throughout the bulk of the film by men. Such objectification is treated playfully and humorously. While it is a different time and place, this is a movie that may (and often does) receive criticism today for such a depiction. However, the very frivolity with which the subject matter is treated serves to highlight the devastating effect this seemingly harmless attitude has on the main characters. It cannot be ignored that, despite all its superficial charm, this is a movie balanced firmly on the last few minutes of its runtime. To judge Gigi without appreciating the significance of the ending is to strengthen the flippant sexism Gaston destroys so completely in asking Gigi to marry him. As is stated in the title song, the miracle of Gigi is indeed that, “overnight there’s been a breathless change”–but it was in Gaston, not Gigi.